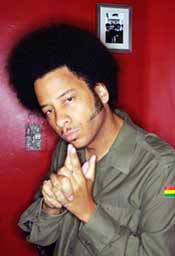

Interview with Boots Riley of The Coup

The stores make money off of very low wages The next time you see two women running out the Gap With arms full of clothes still strapped to the rack Once they jump in the car, hit the gas and scat If you have to say something, just stand and clap ... This goes to all them hard-working women Who risk jail-time just to make them a living We know there'd probably be no one in prison If rights to food, clothes and shelter were given.

With arms full of clothes still strapped to the rack Once they jump in the car, hit the gas and scat If you have to say something, just stand and clap ... This goes to all them hard-working women Who risk jail-time just to make them a living We know there'd probably be no one in prison If rights to food, clothes and shelter were given.

With arms full of clothes still strapped to the rack Once they jump in the car, hit the gas and scat If you have to say something, just stand and clap ... This goes to all them hard-working women Who risk jail-time just to make them a living We know there'd probably be no one in prison If rights to food, clothes and shelter were given.

With arms full of clothes still strapped to the rack Once they jump in the car, hit the gas and scat If you have to say something, just stand and clap ... This goes to all them hard-working women Who risk jail-time just to make them a living We know there'd probably be no one in prison If rights to food, clothes and shelter were given.These lyrics are from the song “I Love Boosters” on the rap group The Coup’s latest release, “Pick a Bigger Weapon.” Boosters are those who make a living by liberating clothes and other items and selling them at discounted prices, instead of at the hugely inflated prices charged by retail stores. The song is homage to people who live a tenuous life and their part in poor and oppressed communities.

The song and the entire full-length release by the rap group are in a line of radical/revolutionary music that The Coup has continued to release since 1993. That year they released their first CD: “Kill My Landlord.”

Larry Hales interviewed a very hoarse, but game, Boots Riley, lead rapper in the group. Though Boots had a concert the previous night in Atlanta, and was headed towards New Orleans where he was slated to perform and meet up with activists from the Common Ground Collective, he was willing to talk and be interviewed. He and The Coup are now on the Pick a Bigger Weapon tour, in conjunction with notyoursoldier.org.

Boots Riley is a communist and was an activist before becoming a rapper. He hails from Oakland, Calif. In the song “5 Million Ways to Kill a CEO,” he says of the city: “I’m from the land where the Panthers grew/ You know the city and the avenue/ If you the boss we’ll be smabbin through, and we’ll be grabbin you/ To say, ‘Whassup with the ra-venue?’”

Boots became active with the Progres sive Labor Party in Oakland at 15 years old. He remembers being

red-baited by teachers in high school and being outspoken then.

red-baited by teachers in high school and being outspoken then.Larry Hales: Many people think of Oakland as synonymous with militancy because of its history. Would that be fair to say, and what’s Oakland like now?

Boots Riley: There are many contradictions in Oakland, like other cities. It’s not synonymous with militancy, people are struggling to get by, that’s why there needs to be a new struggle for basic needs. We need to fight for reforms as part of the revolutionary struggle, but bring a class analysis. Right now, in Oak land, there are no militant organizations at the forefront, like the rest of the country. In the 1930s and 1940s the basic needs were part of the struggle and the Communist Party was one of the organizations out in front. The CP did change, though, especially in the 1950s and 1960s when red-baiting was at its height.

LH: What part do you believe culture plays in revolution?

BR: Culture is expression, how we communicate and get across ideas. It fills the soil and gets people ready.

LH: Before the rebellions in L.A. in 1992, hip hop was at a different point, and its tone and militancy seemed to mirror the righteous anger in the Black community, especially among youth, and especially in South Central Los Angeles, with songs like “Fuck the Police.” Do you think if hip hop was at a different point, the response after the criminal neglect in the wake of Hurricane Katrina would have been diffe rent from youth in the Black communities not in the area?

BR: If artists were really representing where they are from, then the response would have been different, perhaps. A lot of artists from the South do talk about the reality of life in the area. You have to if you come from there, because it’s what you know. Artists have to be relevant, though. It’s not necessarily about being more militant but about being observant and really reporting conditions. But it’s really the record companies. Artists are just trying to make a living, but the record labels control the release of the material. Artists want to make a living and the industry controls by determining what’s popular. A lot of people point to other areas where there was a movement that dictated culture, but there is a lack of a defined movement. When there is a strong movement, culture will follow and the struggle will be emboldened.

LH: I know you’re tired, so I don’t want to keep you long.

BR: Yeah, and I’m losing my voice.

LH: I have two final questions. Were you inspired by the recent immigrant rights demonstrations? And what artists do you think epitomize certain eras of the struggle?

BR: A lot of people were surprised by the immigrant rights demonstrations and inspired. I think Paul Robeson, Gil Scott-Heron, Public Enemy and Bob Dylan epitomize certain eras.

For more information about The Coup, go to thecoupmusic.net.